Insurance: a thing providing protection against a possible eventuality.

For the first 60+ years of the 20th century, people paid for doctor-patient relationships with their own money – or the occasional chicken. Physicians practiced out of their homes, or neighborhood offices, and everyone knew who was a GP and who was a ‘specialist’, which ones were friendly and which ones were brusque, who was good and who was bad, and who was expensive and who was, well, let’s just say less expensive (a factor usually linked to a physicians local reputation for quality)

People went to the doctor when they needed to, but since medical care was so local, the doctor-patient relationship was also rooted in community. We saw each other at the market, and at houses of worship, and knew each other via social networks (the human kind). Doctors made house calls, and a lot of care happened at home; patients with chronic conditions often had special fee arrangements with their physicians. Hospitals were reserved for the most serious problems, surgery or severe functional decline.

In the 1920s, parallel movements began towards “Periodic medical examinations of apparently healthy persons" (JAMA 80: 1376–1381) and the earliest forms of 'health insurance’ (designed to protect against potentially devastating financial losses associated with hospitalization). By mid-century these trends consolidated and took hard root. While the idea of the annual ‘checkup’ has had its ups and downs (cf. Ann Intern Med 95(6): 733-735), the concept and value of screening for illness is now firmly rooted in evidence; however, the original idea of insurance as a financial safety net against unexpected health-related events has become completely uprooted.

This is an important backdrop to the current struggle over social acceptance of the terms of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), because as the health system evolved today, more than 70% of American healthcare expenses are not paid by patients themselves, but are either subsidized by employers as part of a benefit plan (approximately 20%) or paid out of Federal and State government coffers (almost 50%), especially for those citizens over age 65, families with children at risk and adults with special needs. This means we are paying for each other’s care right now.

I have no problem sharing the costs of health for my fellow citizens; but if I am going to do so, I want to make sure that my money is being spent well, or at least not spent unnecessarily (I can think of a few other things I would like my taxes spent on other than a completely preventable stroke and the subsequent physical and neurological consequences). This, by the way, is the fundamental premise of the ACA.

The media debates over the ACA continue to focus on individual premiums, with the opposition bringing the spotlight to those who now have to pay more for coverage. The reason most often cited was that those policies were cancelled because they didn't meet minimal coverage standards set by the ACA.

For a long time, we lived under the illusion of ‘freedom’ with regard to our health coverage: if we needed to save our own money, we could pick and choose features of a health plan, including limited – disaster-level – coverage, in order to reduce our premiums; this often left wellness and prevention services out of the coverage. Unfortunately, the lack of coverage for these services in peoples lives often leads to high rates of largely preventable conditions, or delays in diagnosis so that symptoms reach the threshold of ‘disaster-level” coverage.

I am all for freedom, but since we’re already paying a share of the costs of our fellow citizens medical problems, I can’t support the freedom to delay the diagnosis of colon cancer, acquire bacterial pneumonia, go blind from diabetes or glaucoma or require multiple hospitalizations because you cant get medication regularly. These conditions put limits on freedom that go well beyond anything imposed by the ACA.

Under the Affordable Care Act, health coverage is not just insurance anymore.

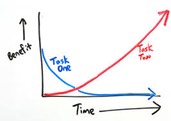

The minimal coverage standards under the ACA are actually mandated services (and the reason some premiums are higher) well established to make us all healthier – and reduce our collective costs over time (allowing other government programs to be better funded, or even, perhaps, allowing our taxes to be lowered once we reached stable levels of population health status). It was these levels of service for prevention and wellness services were often missing in the ‘low cost’ coverage some individuals may have had before.

The ACA basically formalized, and put some discipline behind, the fact that all of us are already sharing healthcare costs across the whole population. The ‘bundle’ of mandatory services required is based on clinical evidence; we know what can help people get better and we also know what kinds of things can help them avoid the emergency room or a hospital stay. While some of the services in the package may be unnecessary for certain individuals (like paying for maternity care for a 50+ year old woman), they are bundled together into the pool. So while my wife is not getting pregnant anymore, I look at that as my contribution to the pool so that some very sick diabetic can get the care they need to avoid a very expensive stay in the intensive care unit and, more importantly, so that the retired school teacher next door – whose daughter is expecting her first grandchild -- can get a flu shot without a bill. Shared risk, shared benefit.

However, one of the biggest challenges the ACA faces is getting people to realize that the real benefit is not about getting coverage, but using it, especially the preventive, wellness and chronic disease management services that will never generate a bill – because their cost is included in their coverage. Medications? Covered. Cancer, blood pressure, diabetes, breast cancer screening? Go get ‘em, and make sure your family, friends and neighbors do too. Help with diabetes, heart disease or smoking? All included.

The real, big league, benefits of the ACA will not be fully realized for a few years. It requires a major shift in thinking: encouraging the use of healthcare services. The path to health does require some action on your part: make an appointment; use the services we are all paying for; don’t just think about health insurance for episodes of illness. Once we are able to change that pattern, and make up for lost time (and care) for millions of people with under-managed chronic illness, the overall cost of maintaining our health will go down; and, by the way, even they don’t, I would surely be just as happy if I (and my friends, family, colleagues) were able to stay healthier longer.

My grandfather used to say he loved paying taxes; he felt we lived in the greatest country in the world and taxes were an important way we all contributed to making and keeping it great. The underlying principles of the ACA have given me a new understanding of what he meant, and, to me, a requiring a minimum mandatory level of coverage where we all share in the costs means that my community, and my country, will have a better quality of health proven to improve workforce productivity and economic vitality. I would rather pay a little upfront – and agree to some measures of prevention – and prevent a big bill coming later. Putting our lives at risk to defend our freedom is a fundamental aspect of American life; but this is not the same as letting people have the freedom to put their own lives at risk when the consequences (and their associated costs to us all) are completely preventable.